INTRODUCTION

During the process of creation, an artist’s work is inevitably affected by —among other things— their previous life experiences, their understanding of the world, ideology, what they ate for breakfast, a recent breakup, etc. This statement may seem obvious or unnecessary, but the implications of such a human element are vast and potent. In instances where the image functions as authority, it is important to acknowledge the human element and examine any resulting bias. The goal of this study is to explore the problems inherent to images as it pertains to representations of the biblical character Jezebel. I argue that, by and large, the modern understanding of Jezebel does not accord with the original biblical text. The vehicle for this misconception is, largely, Jezebel’s visual culture. Therefore, in order to better understand how such a misunderstanding can occur, it is necessary to consider how images function within a culture— an increasingly digital culture. How can such a visual culture and its resulting ideologies be examined? Fortunately, YouTube, Google, and digital media are fundamentally built upon data, and this data may serve as quantifiable indicators of the cultural understanding of Jezebel. The accompanying video piece Jezebel & the Internet highlights many of these modern cultural understandings.

PROBLEMS WITH IMAGES

How do images play into the misunderstanding of Jezebel, specifically in the visual culture of digital media? Before considering the data, it is necessary to consider how images function in society.

In his popular book Ways of Seeing, John Berger argues that the social presence of a woman is different from that of a man (Mulvey makes a similar argument of women in classical Hollywood). Tracking the development of Renaissance religious art, Berger elucidates on the disappearance of narrative sequences. Instead of several panels depicting a story, the narratives were conflated to a single frame or moment. The single moment depicted becomes the moment of shame. Within the conventions of the art form itself, the women become blamed for sin. According to Berger:

““In the nudes of European painting we can discover some of the criteria and conventions by which women have been seen and judged as sights.””

And regarding paintings of Adam and Eve in the garden, he goes on to say:

““The striking fact is that the woman is blamed and is punished by being made subservient to the man. In relation to the woman, the man becomes the agent of God.””

What we can surmise from Berger’s work, is that leading up to visual representations of Jezebel is a cultural convention of blaming women for sin. By depicting single moments, we lose any sense of narrative and complexity. Instead, stories become flat and binary ideologies. But the problem is even more complicated because images also contain inherent bias.

Consider W.J.T. Mitchell who, in his essay There are No Visual Media, discusses the bias toward the “visual” in discussions of art. He argues that there is no merely visual media because more than one sense is involved during the perception of meaning. When we see, we smell, we reflect, we sometimes touch and taste. Referring to media as solely “visual” is too simple:

““The specificity of media, then, is a much more complex issue than reified sensory labels such as “visual,” “aural” and “tactile.” It is, rather, a question of specific sensory ratios that are embedded in practice, experience, tradition and technical inventions.””

What Mitchell is suggesting is that images are complicated things. Not only are they an indiscriminate combination of sensory ratios, but those ratios have something to do with the conventions of a society. But it’s more than just a sensory experience:

“We also need to be mindful that media are not only extensions of the senses, calibrations of sensory ratios, they are also symbolic or semiotic operators, complexes of sign-functions.”

According to Mitchell, we should always consider the symbolic significance of an image because it may vary according to who sees it, and the context in which they see it. John Harvey discusses a similar notion while describing the multivalence of images. In his book The Bible as Visual Culture, he says that images:

““...have little by way of a fixed relationship to knowledge. They can not embody semantic meaning with any precision. In and of itself, an image is multivalent; it can have many possible significations and, therefore, no one in particular. In the absence of information which would otherwise expound or guide our perception and stem the image’s flux, it may be as impenetrable or vaguely suggestive as a word in a language we do not understand.””

The metaphor of image as language is apt, and it is the connection back to the biblical text and Jezebel. For, if images contain inherent sensory ratios, semiotic ratios, and multivalence, then images of Jezebel provide infinite opportunities to reimagine her, retrofit her, and reprove her.

WHO IS JEZEBEL?

If one knew nothing about the biblical character Jezebel, but used a search engine to find more information, the search results would have almost nothing to do with her as she appears in the Hebrew bible. She is one of the few biblical characters to have become her own noun; in the modern world, “Jezebel” connotes a sexually immoral woman. The thesaurus yields results such as “floozy, hooker, and hussy.” The Urban Dictionary returns definitions like:

“ “...Often beautiful, she uses her looks to her advantage to ‘lure in’ her next victim.””

In addition to these search results, “Jezebel” is a line of lingerie, a modern luxury magazine, and a blog geared toward women that initially launched with the tagline “Celebrity, Sex, Fashion for Women.” Thus, there seems to be a colloquial correlation to extravagance and sexual impropriety.

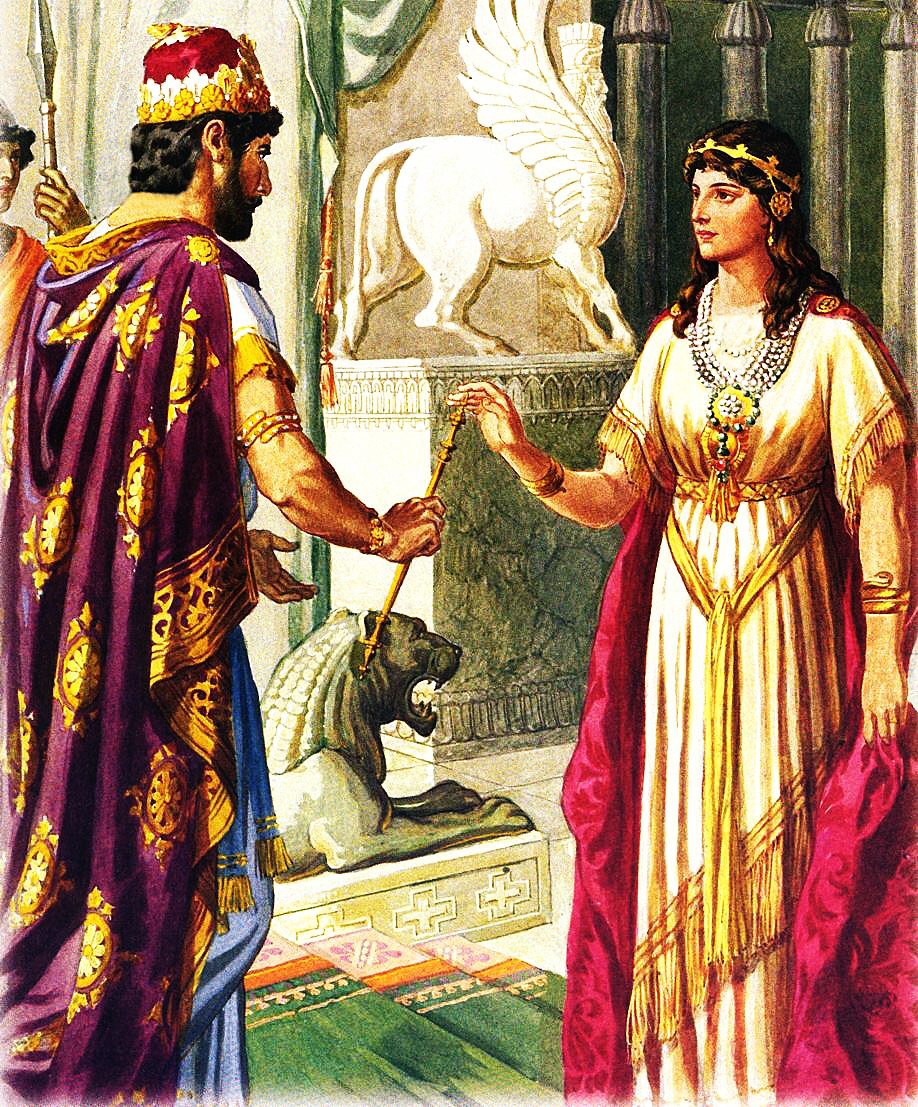

But the appearance of Jezebel in the bible includes no mention of her sexuality. In the Hebrew Bible, Jezebel appears in the books of first and second Kings as the wife of King Ahab— the marriage being a political alliance between Israel and Sidon (a coastal city to the north) where Jezebel was the princess. Jezebel brings her religion to Israel with her, and the worship of Baal is blasphemy in the eyes of the biblical writers. According to the text, Jezebel begins killing Israel’s prophets. Because of this, Elijah challenges the prophets of Baal to a showdown with Israel’s deity. The Baal worshipers fail to summon their deity, so Elijah calls upon Yahweh and fire descends from heaven and consumes the altar. Having won, Elijah then slaughters all of the prophets of Baal. Jezebel threatens kill Elijah by the same time the next day, and, ironically, Elijah retreats.

The next time we hear of Jezebel is during the ploy to obtain Naboth’s vineyard for her husband, who is unable to secure the transaction. She sends letters, with the stamp of the king, to the elders in Naboth’s town, commanding them to lie against Naboth, and then stone him. The elders do so, and after Naboth’s death, the vineyard is claimed for Ahab. Few bible commentators acknowledge the bizarre betrayal of Naboth by his neighbors. If, as is suggested, Naboth’s neighbors had known him since birth and patronized him, how could they turn so quickly? Some scholars argue that this incident highlights Jezebel’s keen understanding of Israelite men. It is perhaps, also, one of the impetus for her modern connotation as manipulator-supreme.

The final time we hear of Jezebel (an entire chapter later) is just before her demise. Having just killed the sitting king and son of Jezebel, Jehu enters town to do the same to her. As she sees Jehu, Jezebel stands at the window, issues one last zinger insult, and then puts on makeup. Jehu commands the eunuchs to throw her down, they do so, and Jezebel is trampled. The donning of makeup is the final impetus for her conception as a whore. The most popular interpretation is that Jezebel puts on makeup in effort to seduce Jehu, but this interpretation is not bolstered by the text. Jezebel is the sitting Queen, presumably old in age by now, and has performed in a political function her entire life. She very likely understands that she is about to die and even issues one last insult as Jehu approaches. A more compassionate reading of the text would indicate that Jezebel, for lack of a better term, “goes out with a bang.”

It is worth noting that nowhere in the text is Jezebel characterized as promiscuous or seductive. The text makes no mention of her physical appearance. Unlike characters such as Rachel, Joseph, and Rebekah, whom the Bible explicitly labels as aesthetically appealing, there is no such indication for Jezebel. In fact, if anything, the text indicates that Jezebel is an all-too-loyal wife —even capable of murder. She is not an admirable character by any means, however, it is critical to highlight that nothing about her modern connotation is exemplified in text.

A SURVEY OF MODERN UNDERSTANDINGS

The accompanying piece to this article is a video entitled “Jezebel & the Internet.” The video animation recreates the pages of popular platforms (Google, YouTube, Thesaurus.com, Urban Dictionary, etc.) and features actual entries, comments, and view counts. It is a recreated first-person experience of learning about Jezebel using search engines. The piece ends with a total view count of all clips featured throughout; the total is over 1.5 million (This number only indicates the total views, which inevitably grows by the month. I am not including number of comments, shares, likes, or dislikes in this total). Without counting the superfluous interactions, the videos featured within the animation have been seen at least 1.5 million times, and interacted with by an inevitably higher number. Since the video highlights actual comments, interactions, and view counts, it is a viable ethnographic survey of modern cultural understandings of Jezebel. An analysis of Jezebel & the Internet will reveal several recurring themes and motifs. We shall explore two of these tendencies now.

Jezebel’s prominent association is that of a sexual essence. Consider authoritative sources such Thesaurus and Urban Dictionary which return results like “whore,” “harlot,” “slut.” This idea is advanced by spokespersons who, by nature of their occupation, also function as authorities. Jezebel & the Internet features TV show hosts, priests, and preachers who all drive the notion that Jezebel is sexually immoral. We must not forget that, in addition to the bias these opinions express, the videos are themselves images and operate in a multivalent manner.

Another significant tendency highlighted in the video is Jezebel’s retrofitting onto modern situations. She is often modified to align with a contemporary issue. For example, a video called President Jezebel uploaded in 2016 to the YouTube channel “Wild Bill for America” has 6,258 views and over 100 comments —all of which agree with Bill regarding the sentiment that Hillary Clinton was “poised to go from being an Obama minion to full fledged president Jezebel.” In this case, an ancient text is interpreted within a modern context and modified to demonstrate a political affiliation and ideology.

As an ethnographic survey, the video Jezebel & the Internet demonstrates of various modern uses of the word “Jezebel.” We have explored two tendencies (a potentially false correlation to sexual impropriety and the retrofitting of Jezebel onto modern women); we have also noted that the videos have been engaged over one million times. Although outside the scope of the current study, an in-depth examination of the comments section would yield demographic details about the interactions: which users are commenting, whether they agree, and to which additional channels they are subscribed. Often they are subscribed to channels featuring similar subject matter, and thus it is easy to imagine how confirmation bias can persist among digital communities. Andreas Ekstrom often discusses digital bias and the philosophical impossibility of search engines to return “knowledge.”

CONCLUSION

In order to combat many of these inconsistencies and biases, there is a need for new language and vocabulary. Regarding “visual” media, Mitchell proposes a need for a new language and taxonomy. In her article Blindness and Visual Culture: An Eyewitness Account, Georgina Kleege describes the overwhelmingly negative connotations of vernacular regarding the blind. Regarding new language, she says:

“And as we move beyond the simple blindness versus binary, I hope we can also abandon the cliches that use the word “blindness” as a synonym for inattention, ignorance, or prejudice.”

Jezebel has been interpreted in many and various ways throughout the centuries. This paper has highlighted, what I argue to be, several inconsistent representations of this biblical figure. In addition to her multivalent interpretations, we have also explored how images are themselves multivalent —capable of conveying meaning within various contexts. These meanings are demonstrated by what W.J.T. Mitchell calls sensory and semiotic ratios. Furthermore, John Berger and Laura Mulvey describe the errors of conventions by which women have been represented in art. Once these images become available through the internet, they are capable of circulation amid the confirmation bias of connected communities.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

America, Wild Bill for. “President Jezebel.” YouTube, YouTube, 19 Apr. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=tW0D17GwU0A.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing: Penguin, 2008.

Deez, Genie. “Jezebel & The Internet.” YouTube, YouTube, 27 Feb. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=aogkRTTGmto.

Ekström, Andreas. “Andreas Ekström.” TED, www.ted.com/speakers/andreas_ekstrom?language=en.

Gaines, Janet Howe. Music in the Old Bones: Jezebel Through the Ages. Southern Illinois University Press, 1999.

Harvey, John. The Bible as Visual Culture: When Text Becomes Image. Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2013.

www.thesaurus.com, www.thesaurus.com/browse/jezebel?s=t.

“Jezebel (Website).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 16 Apr. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jezebel_(website).

“Jezebel.” Urban Dictionary, www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Jezebel.

Kleege, Georgina. “Blindness and Visual Culture: An Eyewitness Account.” Journal of Visual Culture, vol. 4, no. 2, 2005, pp. 179–190., doi:10.1177/1470412905054672.

Mitchell, W. J.t. “There Are No Visual Media.” Journal of Visual Culture, vol. 4, no. 2, 2005, pp. 257–266., doi:10.1177/1470412905054673.

Rose, Rachel, and Laura Mulvey. Laura Mulvey 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema' 1975. Afterall Books, 2016.